We have often reported here that targeted nanoparticles to treat cancer have shown great promise in animal studies. An MIT news release written by Anne Trafton now informs us that “Targeted nanoparticles show success in clinical trials“:

Targeted therapeutic nanoparticles that accumulate in tumors while bypassing healthy cells have shown promising results in an ongoing clinical trial, according to a new paper.

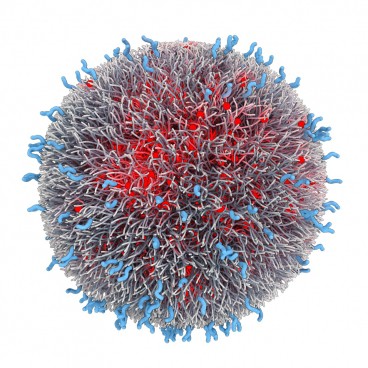

The nanoparticles feature a homing molecule that allows them to specifically attack cancer cells, and are the first such targeted particles to enter human clinical studies. Originally developed by researchers at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, the particles are designed to carry the chemotherapy drug docetaxel, used to treat lung, prostate and breast cancers, among others.

In the study, which appears April 4 in the journal Science Translational Medicine [abstract], the researchers demonstrate the particles’ ability to target a receptor found on cancer cells and accumulate at tumor sites. The particles were also shown to be safe and effective: Many of the patients’ tumors shrank as a result of the treatment, even when they received lower doses than those usually administered.

“The initial clinical results of tumor regression even at low doses of the drug validates our preclinical findings that actively targeted nanoparticles preferentially accumulate in tumors,” says Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor in MIT’s Department of Chemical Engineering and a senior author of the paper. “Previous attempts to develop targeted nanoparticles have not successfully translated into human clinical studies because of the inherent difficulty of designing and scaling up a particle capable of targeting tumors, evading the immune system and releasing drugs in a controlled way.”

The Phase I clinical trial was performed by researchers at BIND Biosciences, a company cofounded by Langer and Omid Farokhzad in 2007.

“This study demonstrates for the first time that it is possible to generate medicines with both targeted and programmable properties that can concentrate the therapeutic effect directly at the site of disease, potentially revolutionizing how complex diseases such as cancer are treated,” says Farokhzad, director of the Laboratory of Nanomedicine and Biomaterials at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, associate professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and a senior author of the paper. …

The news release goes on to detail several features of these nanoparticles that may be useful in evaluating other types of nanoparticles that are currently at earlier stages of development and have only been tested in animal models. First of all, nanoparticles of many different compositions have been developed, from gold to DNA. These, called AccurinsTM, use clinically validated biocompatible polymers and incorporate a “stealth” layer to avoid removal by the immune system. As explained in the news release:

One of the challenges in developing effective drug-delivery nanoparticles, Langer says, is designing them so they can perform two critical functions: evading the body’s normal immune response and reaching their intended targets.

“You need exactly the right combination of these properties, because if they don’t have the right concentration of targeting molecules, they won’t get to the cells you want, and if they don’t have the right stealth properties, they’ll get taken up by macrophages,” says Langer, also a member of the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

The BIND-014 nanoparticles have three components: one that carries the drug, one that targets PSMA, and one that helps evade macrophages and other immune-system cells. A few years ago, Langer and Farokhzad developed a way to manipulate these properties very precisely, creating large collections of diverse particles that could then be tested for the ideal composition.

“They systematically made a set of materials that varied in the properties they thought would matter, and developed a way to screen them. That’s not been done in this kind of setting before,” says Mark Saltzman, a professor of biomedical engineering at Yale University who was not involved in this study. “They’ve taken the concept from the lab into clinical trials, which is quite impressive.”

The systematic way in which these researchers addressed multiple variables and issues gives us some indication of what will be required to move nanoparticles and other nanotherapeutics from laboratory studies into clinical trials.

—James Lewis, PhD