Summary

In this session, James Peyer, the CEO and founder of Cambrian Biopharma, shared his overview of the longevity biotech industry with insights into what it actually means to be a longevity biotech company, how Cambrian functions, what is a DisCo model and why it will most likely replace single asset biotech companies model, and also the barriers that he sees are preventing us from starting clinical trials with the first geroprotectors. In the end he also presented a preview of a paper calculating the potential societal value of geroprotectors.

Presenters

James Peyer, Cambrian Bio

James Peyer is the Chief Executive Officer and Co-Founder of Cambrian Biopharma. He also serves as the Chairman of the Board of Sensei Biotherapeutics and board and executive roles across Cambrian’s pipeline. He has spent his…

Presentation: How to Fund and Build Geroprotectors

- Cambrian is a DisCo (Distributed Drug Discovery Company) structure, so a single biotech that acquires and develops other biotechs underneath us. So not quite a company building studio, not a traditional pharmaceutical company, definitely not a VC, but a kind of mixture of all of those three things.

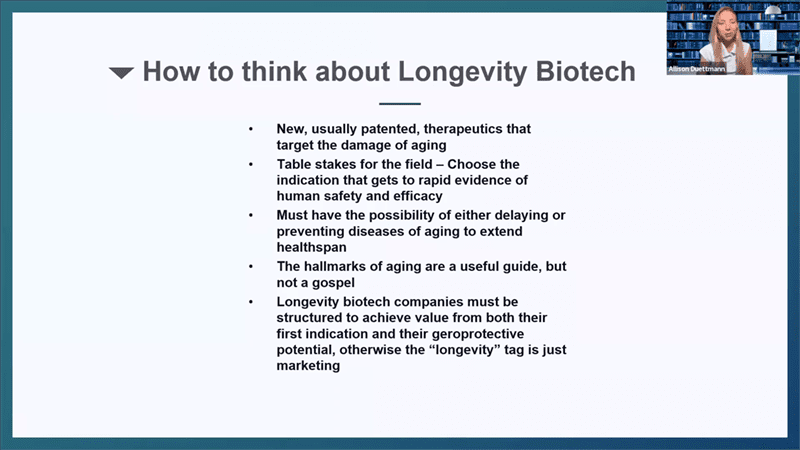

How to think about longevity biotech

- What actually defines a longevity biotech company? I define it as private companies, almost always for profit, that are taking new usually patented therapeutics that target the damage of aging. And that’s the key, it doesn’t matter what’s the first indication, usually it is not directly aging at first, but it needs to target the underlying damage of aging. At Cambrian, we also have an extra caveat that it also must be at least in theory possible to turn it into a preventative drug – so it should be at least in theory possible to use it in healthy person and prevent them from getting sick instead of waiting for them to get sick and then try to unwind that.

- Tablestakes around indication selection. Before 2015 or so, longevity biotech was kind of described as the people who want to do clinical trials in healthy older people to slow down aging and I think that’s not the investible moat for this field. The way the industry is shaping up right now is that if you have a molecule that can target the damage of aging, people are choosing whichever indication or disease that gets the most rapid evidence of human safety and efficacy. And once you have that, the presumption is that you can take this drug and run a clinical trial in healthy people and prevent them from getting sick.

- Cambrian and most of the other multi-asset companies have organized themselves around the hallmarks of aging as the main organizing principle. Hallmarks are a useful guideline, but are really not a gospel, so we don’t spend a lot of time inquiring directly about which hallmarks specific drugs target – I think that’s an unhelpful way to think about it. Hallmarks of aging basically bundled all the different competing theories of aging because there was sufficient evidence that no one of those theories were sufficient to explain all of the data that we were starting to get about extension of mammalian lifespan, therefore elements of all of these things had to be true.

- Longevity biotech companies must be structured to achieve value both from their first indication and then from their geroprotective potential later, otherwise the longevity label is just marketing. Most biotechs are built to get bought in their late clinical stages. With the current approach of getting approached by big pharma companies in later clinical trial stages, if the companies do not structure their trials in a way that goes towards the geroprotective potential, they will fail and not deliver on their longevity promise. The chances that the big pharma company will run the geroprotective trial is nearly zero. So unless you’re setting up the company to be sustainable enough to make decisions about which trials to run after the first approval of the drug, it’s not really gonna have a big impact on the geroscience space.

Q&A

What are your main drug discovery challenges now? Target discovery, medchem, synthesis, assays, etc.? And how are you addressing these?

- I don’t see target discovery as a problem. Most of the assets that we are bringing in are at the hit to lead or lead to candidate stages, there are some opportunistic assets at IND stages that we are keeping an eye on. So we spend most of our time building the R&D execution teams and building the chemistry, preclinical validation and then bring as many INDs to the floor as possible. The way I think about Cambrian is as an engine where we input longevity science and output as many INDs as possible from that. We are starting our first few IND enabling studies this year and aiming for 4-6 new INDs every year for dramatically different programs going forward.

Are you also in parallel going to do aging model experiments like worms or something that is not mice?

- We actually have collaborations already set up for worm longevity experiments as a quick and easy validation whether it affects lifespan. And then as we move towards candidate selection, I see mice longevity studies as something we will be doing in parallel with clinical trials with every program that we push forward. That way we can be more and more ready to understand the value getting close to that first approval or Phase 1 or Phase 2 safety efficacy study and then being able to pivot into this geroprotector space as soon as humanly possible without needing to do additional preclinical validation work.

How useful are orphan diseases that mimic certain aspects of aging to target from a financial perspective? (e.g Battens disease, progeroid syndromes, etc.)

- I have two very different answers. This topic of indication selection is probably something that Cambrian and before at Apollo we did best, that’s what they know well. Picking an orphan disease that is directly related to the mechanism that you’re targeting with whatever drug, is really useful and I am optimistic about that approach. An example is Aeovian Therapeutics that we did at Apollo, which is an rapamycin analogue and we basically found a mTORopathy – a disease in which mTOR was specifically overactivated, and positioned the drug to first go into that orphan disease. And that was exactly the right thing to get the safety and efficacy data in as fast and de-risked way as possible. However, progerias almost never fit that definition. My view is that the damage from progerias doesn’t mimic natural aging damage well and to do an aging slowing trial in progerias is a very uphill battle and still requires very long term trials that are not ideal for our purpose. So I have been less enthusiastic about progerias as a general way for testing geroprotectors.

How do you plan to prevent acquiring companies from ignoring the broader-than-initial-indicitaion potential of assets?

- For Cambrian that is really easy as we are the majority owners – as long as we are the owners, the pipeline can be moved and pushed in that direction. We also usually don’t have separate CEOs for those companies, it’s one single R&D team pushing together all of the assets that are held in the companies underneath.

Does that mean that you are going to shy away from selling assets?

- That’s right. Not entirely and there might be some exceptions, but Cambrian is designed to be the new Genentech or the new Novartis, not the biotech that comes up and then sells its drug to the Genentech or Novartis. We might be able to do long-term partnerships where we still retain control of the second and third indications, but I think that the way we capture this space is by building something really big and really long lasting.

What is DisCo?

Distributed

drug discovery company, usually a C-corporation, structured like a

single biotech company and not like a fund, with many different shots at

the goal. Usually takes majority, but not usually 100% stakes of equity

in a group of subsidiaries. Cambrian has 14 different assets in

development. That means 14 different companies with 11 majority stakes

(between 50-90%) and 3 minority stakes, which we call investments.

Another characteristic is that there are some centralized functions

like acquiring assets, launching or starting new programs, building them

out, infrastructure functions like taxes, financing, legal, IPs,

fundraising, medicinal chemistry, IND enabling studies, general

management – all of that doesn’t have to be replicated 15 times over,

you can have just a single group of people that are very good at their

job and do it for most of the assets that are developed underneath the

DisCo.

The 2 big functions that are distributed are the 1) biology –

particularly what our scientific founders and teams with whom we are

starting new companies have deep knowledge in and we don’t. That stays

within the subsidiary company. 2) The first indication specific to that

company – that needs a specific clinical team around each asset. So

there are some functions in the hub, and some functions in the spokes.

How are discos different from VC funds?

- Time horizons. VCs raise money from investors and then they need to

return the money in 7-10 years, during which the fund is supposed to do

an X multiple. DisCos have no timeframe, the whole disco itself is a

company that can go public and therefore can live sustainably in an

enduring way as long as the value of the underlying assets is worth it. - DisCos usually take bigger stakes than VCs, usually majority (more

than 50%, partly because of the US security regulations introduced with

the Investment act in 1940 that prevents someone from listing a VC fund

on an exchange). - The assets on a program by program basis usually do not raise money

on their own, compared to classic VC process where you go through the

loop of seed, series A, etc. with every asset. With DisCos we just

decide whether we want to do the Phase 2 study from the sum of money we

have or not. - Even funds are moving towards this model now. If you look at some big biotech funds like Flagship Pioneering or Third Rock Ventures

that started the initial company building VC approach, they are moving

towards this model with bigger and bigger financing rounds and taking on

more and more projects because of some of the advantages (ability to go

public, ability to centralize the assets and reduce the risk of any

single program failing).

Discos vs normal biotechs or pharma companies?

- A lot more programs, we don’t think about ourselves as a platform

for a single technological set of innovations that spawns drug

development programs, but more as an engine that can take in substrate

and create new companies and programs from that. - We can do something interesting with our scientific founders that

better solves the “equity split problem” in multi asset companies. When

you have two different scientific founders of different companies

getting acquired by a multi asset company and getting the same equity

split in the multi asset company, it is usually a problem because each

scientist feels like their projects are worth more than the other

projects. With DisCo each scientific founder has their own company and

ends up with a bigger stake, and they don’t have to try to value all the

other assets in the DisCo. - And the second problem it solves is the “relay race problem” – if

you are a scientific founder, you made a discovery, but that’s just the

first phase of the process, developing a drug is a team play, and you

need a team for each different stage. Cambrian has all those teams

inhouse, so scientists can focus on their specific area instead of

taking on a role they don’t want to have. Therefore there is also no

reason for them to be violently replaced by executives just because the

scientific founder might not be best in that executive role – they just

don’t have to take on it at all. This makes the scientific founders much

more engaged and motivated to stay along for the ride.

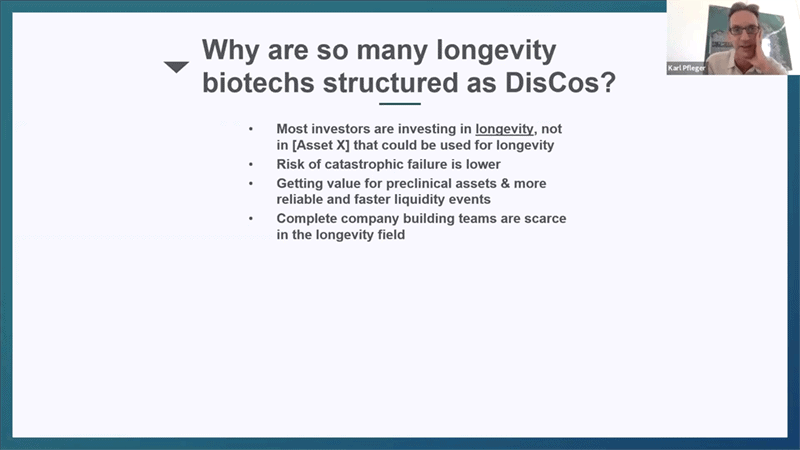

Why are so many longevity biotechs structured as discos?

- Cambrian, Juvenescence, Life Biosciences, and a

series of other groups that are trying to take these multi-shots on goal

approaches and I would even argue that the majority of venture funding

coming into the space is coming into structures like this. I have 4

thoughts and reasons why that might be:- Most of the investors that are coming into the space

are investing into longevity, not asset X (this technology is going to

be the game changer in senescence), they want to invest in the general

thesis (this field of medicine is going to change medicine and the way

we approach aging) – so companies that can capture the general thesis

are more successful as they are better suited for investment. - The risk of catastrophic failure in biotech is much

lower in DisCos – many more shots at the goal. If you have 15-20-30

programs in development and the resources to fund them then the chance

that none of them are successful becomes much smaller compared to single

assay biotechs, unless there are core issues at play in the execution

of those programs. - We’re living in a world where preclinical and early

clinical stage assets are going onto public markets quicker and quicker

and getting more and more value. But people have a hard time getting

those preclinical assets right, therefore with a DisCo that has

experience with it, the risk distribution is much better. If you have

more than 15 assets in the preclinical phase, the chance that at least

one of them is approved is above 95%. So that way you can capture more

of the real value of the risk adjusted NPV (net present value) of

preclinical assets earlier. - Complete company building teams are really scarce in

the longevity field – you need to have differentiated science, the

experience and knowledge which target to choose, get your IND enabling

studies in a row, take that to clinical trials, successfully execute it

and raise all the money along the way. This is what VCs are complaining

about most of the time, that there is a lot of money but not enough

teams. DisCos are kind of a solution to that problem with specific teams

and focus areas.

- Most of the investors that are coming into the space

Q&A

Do you think that we’re going to get an explosion of DisCos, both in and out of longevity space? And do you think all DisCos are going to just grow up and become new Novartises and Genentechs or do you think that some of them are going to be bought by mega pharmas?

- I think that this model will over time replace the single asset model, but not platforms. So the companies that will be going public in the near future are most likely going to be either DisCos or big platforms. DisCo doesn’t replace the platform model. Are each of them going to be the next Novartis? No, lot of them that are not in the longevity space will make their bacon by maturing a program through Phase 2 clinical trials and doing M&A to partner that program to big pharma company and then reinvest that their early stage R&D capabilities. We might do that with Cambrian from time to time as well, but I think that if we have the space not to do that, it is better because the value really comes in the 15-20 year timeframe as opposed to the 5-10 year timeframe.

Are most of your companies platforms or single asset companies?

- Most of them are single assets, not platforms. But it depends on how you define a single asset, we have a conservative view of that – for us a single asset means it is utilizing one set of scientific discoveries and even if there are multiple shots at the goal, if the scientific discovery turns out to be not true, they all fail.

Can you join a DisCo as an individual contributor, do you need a big team, or how does that work?

- If you’re asking whether we are hiring then yes, constantly. DisCos tend to be big companies because of all the different functions that we are covering. Working at a DisCo for an individual in the end is not that different from working at a different biotech. The difference is where people contribute – Cambrian has 4 different teams – Ventures team (inhouse VC – finding scientists, forming new teams), R&D team (advancing from hit to lead, and other stages, etc.), Operations team (everything else that it takes to build a biotech company), Individual group teams. So there is an opportunity to get involved in any of those pieces. All that in total makes about 105 people on our payroll right now, and we started 2 years ago.

How do you distribute value/recognition among the scientific founders if an individual drug program is a success or fail in the DisCo model?

- Individual success sits with the scientist in the DisCo model much longer than in the standard biotech model approach that can pivot around all over the place or get absorbed into an R&D company, because they own larger stakes in their assets compared to the standard model.

- Regarding the recognition, it’s much more about the culture of the organization. When building a DisCo, it’s important to build a culture about celebrating forming useful hypotheses worth testing and celebrating even if the test fails. “It’s really great that we did that because now we know that this doesn’t work.” Then the whole team feels like they are advancing something bigger.

Is there an example of a DisCo in another sector than longevity, that was formed longer ago (>5y, ideally >10y) and has grown and prospered in the way you foresee for Cambrian etc?

- BridgeBio is my favorite mature example of this model (founded in 2015). When I talked to investors like Cambrian, I pitched it as BridgeBio but for longevity. If you look at the evolution of this model, a lot of it was an evolution of the model started even earlier than 2015. Companies like Nimbus therapeutics, some of them evolved from IP holding companies into these hub and spoke models. And then it merged with Third Rock Ventures and Flagship Pioneering approach. They are some of the most consistent VC funds in the biopharma world and they incubate companies inhouse, put a lot of capital into them (usually all the seed and series A rounds – like $50M) before they let anybody else in, and then let them fly out. And it was a sort of natural progression because it was just so expensive to build the structure around a new company every time for each asset.

Thoughts on acquiring companies to exploit potential synergies with different combinatorial therapies for single interventions (cell therapy+senolytic for osteoarthritis)? It would be difficult to do that for single asset companies, but it seems more suitable to do for DisCos.

- You hit a nail on the head here. In 15-20 year timeframe combinations are going to be the most important thing. In general as we get more and more drugs approved as single agents, then the next bridge is biomarker enabled single agent clinical trials in multimorbidity risk prevention – slowing aging trials. The effect we are going to see from single agents would be hopefully significant (5 years of healthy lifespan extension would be a massive boost already), but there is not going to be a single silver bullet for aging. In order to get really large effect sizes, we will have to think about combinations as early as possible. And we will be trying to do trials with combinations and combinatorial studies in animals later once we get to the scale. The ITP that the NIH is running have already started to do some very preliminary work on that, like rapamycin and metformin – which actually works better together than any of them individually. And I hope that as we get to patented and more potent drugs, we will see more accentuated synergies.

Why do your candidate drugs must target particular aging hallmarks? Would it be better that they target the biological age? Targeting a particular damage form may be misleading, as aging is the reflection of many damage forms. The biological age may reflect these many damage forms, whereas it is much harder to do with hallmarks.

- Agree, as I said, hallmarks are a useful guideline for us to classify the biotechs we are evaluating, but it’s not something that is required. If we had a drug that we see can slow epigenetic aging, that alone is interesting for us as well.

Barriers preventing us from starting clinical trials with the first geroprotectors

- I like to think about the space as operating along two simultaneous swim lanes that are going over the next decades. The last decade was about discovering methods to extend lifespan in mice, and as a field, we’ve done that pretty successfully.

- Right now in this decade there is one group of people (longevity biotech) that is showing safety and efficacy of these different medicines in human clinical trials. And then there is the second group developing a clinical pathway for age slowing medicines. And I have been a huge advocate for starting things like the TAME trial and any TAME like trial that is doing two things at once: 1) trying to measure whether the intervention can slow the onset of age related diseases in a human population, 2) simultaneously correlate that interventional trial to a biomarker or composite biomarker of multimorbidity risk that the FDA could later use to justify accelerated approval for trials in otherwise healthy individuals.

- And only when those two things come together: 1) safe and effective medicines entering the market with potential geroprotective medicines + 2) clinical pathway with well controlled interventional studies, we can get to the point where we can start approving age slowing therapeutics to be used in healthy people.

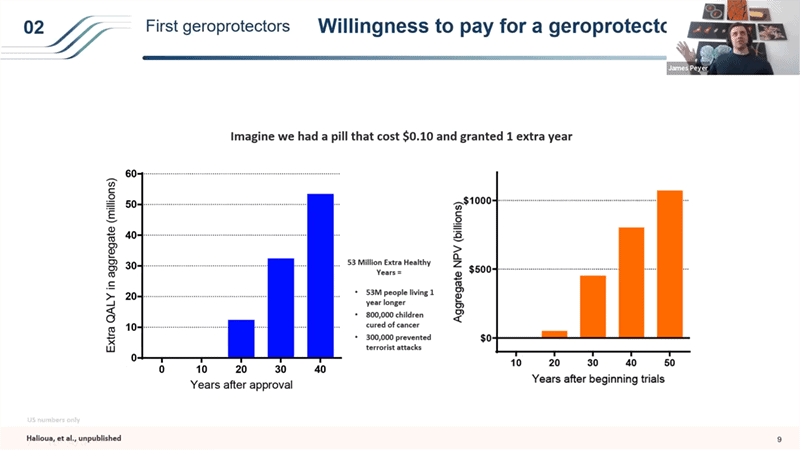

- Which raises an interesting question that I and Celine Halioua from Loyal wrote a paper on together, that is yet unpublished but hopefully published soon: What is the value to society of a geroprotector of different efficacies in terms of risk discounted net present value?

- So for example what if Metformin turns out to be a decent but very weak geroprotector and only extends the human lifespan for 1 year. What is that worth? So if we had a $0.1 pill, which is what Metformin costs, that amounts to about $70 a year and 1 extra year of life – you would generate just in the US about 53 million extra quality adjusted life years by treating people over 55 in the 40 years after the approval. That’s like 800,000 children cured of cancer or 300,000 prevented terrorist attacks. Even more interesting is the aggregate net present value. It takes a really long time to start showing value, but it’s huge in the end. 50 years after you start the trials, the drug that extends life by just 1 years is worth a trillion dollars over those 50 years.

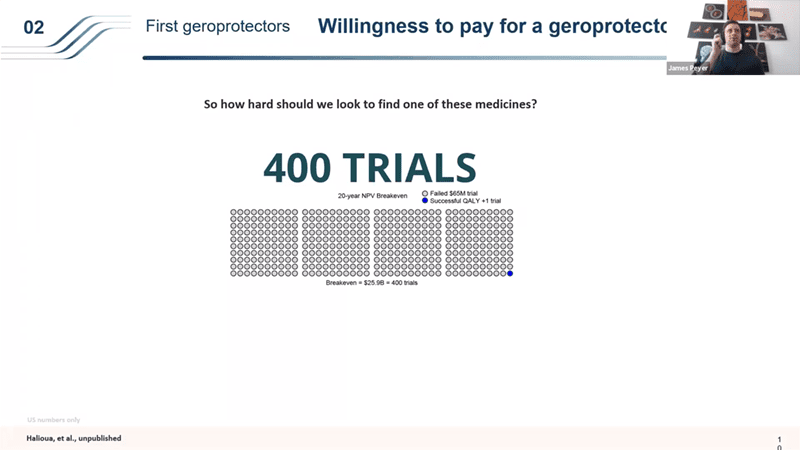

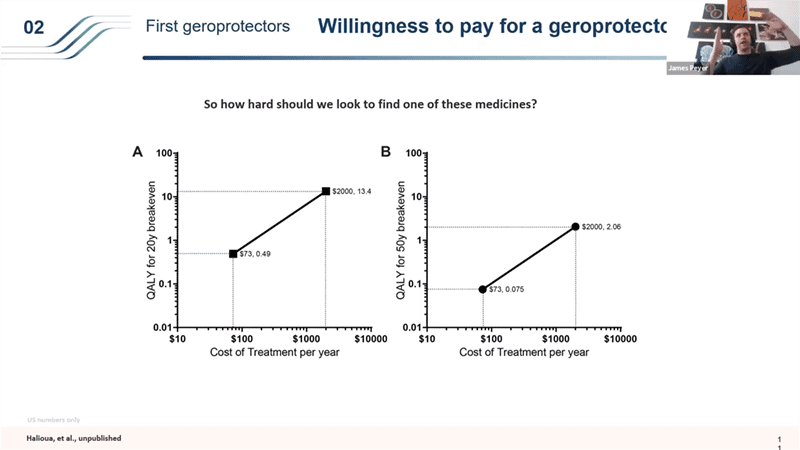

- So what that means is that even if you take just the 20 year view for drug like Metformin that would extend life by just 1 year, it would be worth running 400 trials each costing $65M in which 399 of them failed (from breakeven money in and money out point of view with a fairly conservative views – we valued 1 QALY at way less than what modern gene therapies are getting reimbursed for from insurance companies are valuing it at).

- This is an interesting analysis but it has an even more interesting twist that I wanted to point out in order to show the importance of running trials like TAME with cheap interventions first.. Generics are important because the price element is so important in the roll out.

- So if you take the same 20 year timeframe where you have to get your money back for society in the first 20 years of setting up a bunch of different trials, if you have a drug that costs like a $70 a year like Metformin, the threshold for breaking even for the investment you make to distribute and get this drug into millions and millions of people is very low. Anything over 0.4 extra QALYs (so shifting lifespan from 80 to 80.4 years), if you do better than that, it is worth it as an investment for society. But it’s a very price sensitive structure that people don’t usually think about. Because you’re treating people for so many years before you see the benefit of this, if you increase the price to $2000 a year, (which is interestingly about what Lipitor cost – statins when they are under a patent cost around that price), the bar becomes so much higher for that breakeven point – you would need to be delivering more than 13.4 extra QALYs to be break even within the first 20 years (if you have 10 years long clinical trials). And that then changes dramatically if you have shorter time frames in the clinical trials or longer timeframes for the break even point.

- The point that I wanted to bring up with this is why it is so important to start with generics – this price element plays a huge role in how a drug like this would get rolled out. So these philanthropic trials with generics can set a very nice bar for us and as soon as you lower the clinical trial timelines using those generics, then it changes the models dramatically and we can start running these patented drug trials in the 2030s.

- It is a powerful way to look at the topic. Also Andrew Scott has recently published a great paper using the “willingness to pay” metric.

Q&A

Can you walk us through the relationship-building that goes into the formation of a new subsidiary? How do you discover new projects and develop a rapport with the new teams?

- Still a huge amount of relationship building, the team you’re building the company with is probably the biggest risk factor for success or failure. So we spend a lot of time with the scientific founders before launching a new program. At the same time we have the benefit of a team of operators with whom we’ve already built a number of programs before, so there’s more cohesiveness whether or not that program itself is successful – which brings us back to the necessity of honesty and culture valuing celebration of failure.

Any comments on public perceptions of the current longevity scene, e.g. this week’s Newsweek “Young Blood” cover story? This is a major issue that needs to be addressed early, or serious resistance/backlash may develop in the years to come.

- Not a PR expert, but I do really like to talk about the space, and I talked a lot within the investment and broader community around it. There is a perception that the time is here for longevity biotech as an industry. The sequence of going for indication first by targeting the damage and then eventually going to treat healthy people to slow down their aging and not get a disease – it’s starting to pass the bullshit detectors for scientists, investors, and other people. I try not to use comments on the internet as a barometer for the perception of the general public.

- I do however think that “aging is a disease” is a distraction. It does not need to be considered a disease, it might be helpful for us to think about it that way, but there’s no regulatory and investment thesis roadblock with that, which is good because we don’t have a political risk of needing to label aging as a disease to get further.

How can this group help you?

- I don’t have any particular asks. Building a community around this and sharing views and opinions is the biggest thing we can do for each other probably. In fields like ours what tends to happen is fracturing about minutiae, but what has been gratifying in the space is that we see people rooting for each other even if there is a disagreement about some details, because we have an alignment in the mission.

Seminar summary by Bolek Kerous.