Using the enzyme DNA ligase and small DNA strands as building blocks provides an efficient and less expensive path to a large variety of DNA scaffolds and other structures.

Linking together small DNAs to build more diverse DNA nanostructures

Using the enzyme DNA ligase and small DNA strands as building blocks provides an efficient and less expensive path to a large variety of DNA scaffolds and other structures.

Even without special designs and coatings to promote stability, simple DNA nanomachines can survive in human serum and blood for hours or even days, much longer than expected from previous studies using bovine serum, which has more damaging nucleases than does human serum.

At the 2013 Conference George Church presented an overview of his work in developing applications of atomically precise nanotechnology intended for commercialization, from data storage to medical nanorobots to genomic sequencing to genomic engineering to mapping individual neuronal functioning in whole brains.

Programmed assembly and disassembly of rigid 3D DNA origami objects has been achieved by designing complementary surface shapes based upon weak stacking interactions to create simple nanomachines.

Linking proteins to DNA scaffolds to produce complex functional nanostructures can require chemistry that damages protein function. A new systematic approach avoids exposing proteins to damaging conditions.

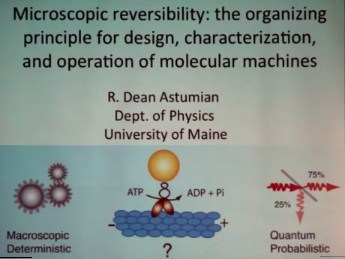

At the 2013 Conference Dean Astumian contrasted macroscopic machines at static equilibrium and molecular machines at dynamic equilibrium, and presented information ratchets and microscopic reversibility as the organizing principle of molecular machines.

DNA sequences designed to either stimulate a specific immune response or to down-regulate an undesirable response deliver superior performance when organized on nanoparticles to reach their intended cellular targets.

Gold nanotubes engineered to a specified length, modified surfaces, and to have other desirable characteristics showed expected abilities to enter tumor cells in laboratory studies, and to distribute to tissues within live mice as intended.

Single-molecule spectroscopy makes possible adding one rung at a time to a foundational rung grafted to a surface to make a long nanotube scaffold of predetermined sequence.

Positioning two or more molecules along a long DNA strand can cause the DNA molecule to adopt different shapes if the molecules interact. Quickly and cheaply separating these shapes by a simple gel electrophoresis assay provides a wealth of information about how the molecules interact.